How to avoid iterative software development mistakes, explained in 5 pull requests

It doesn't matter whether you call it Agile, Sprint, Shape Up, or something else. The premise of iterative software development is this: until you've built the product, you don't really know what it should look like or how to best build it. You've never used it, so how would you know how it works best? You also haven't built it yet, which means you don't have experience building it. Chances are low that you can accurately predict how its development will go.

So what you do is you acknowledge that you don't know and lean into that. You don't plan the development of the product from start to finish in every detail. You don't nail down and define the hundreds of steps it will take to go from zero to fully-built, shipped, and launched product. Instead, working in iterations, you define roughly where you want to go and take a single small step. Then you look around, get your bearings, correct course if necessary, and take another step. Build something, ship it, learn, build again.

But there's one huge problem with this approach: if you're constantly taking small steps and adjusting the direction slightly, you feel productive even when you're going in circles. You keep taking two steps forward and two steps back but never take a big leap to someplace else entirely.

You end up on a local maximum: you're at a point that's higher than where you were before, but when you zoom out you see that there are higher points. The product is better than it was in a previous iteration but not yet the best one it could be.

And even if you realise that you're stuck and know that you must take a big leap, it's hard to abandon the things you've built in many, many small iterations. "So much work went into this! We can't simply delete it! Right?" Right, says the sunk cost fallacy; the trap in which you continue doing something mainly because you already put a lot of effort in, even if continuing might not make sense anymore.

"We can't simply delete it, right?" is also exactly what went through my head when we threw away a functioning, shipped, customer-validated prototype of 10k lines. Even now, with the question answered with "yes, we can," I find it hard to believe we built and shipped Batch Changes the way we did: building it twice, renaming it twice. But it is one of the most rewarding and customer-focused processes I've been a part of.

The following five pull requests tell the story of how we embraced iterative software development and avoided these two dangers — local maximums and the sunk cost fallacy — to build Batch Changes.

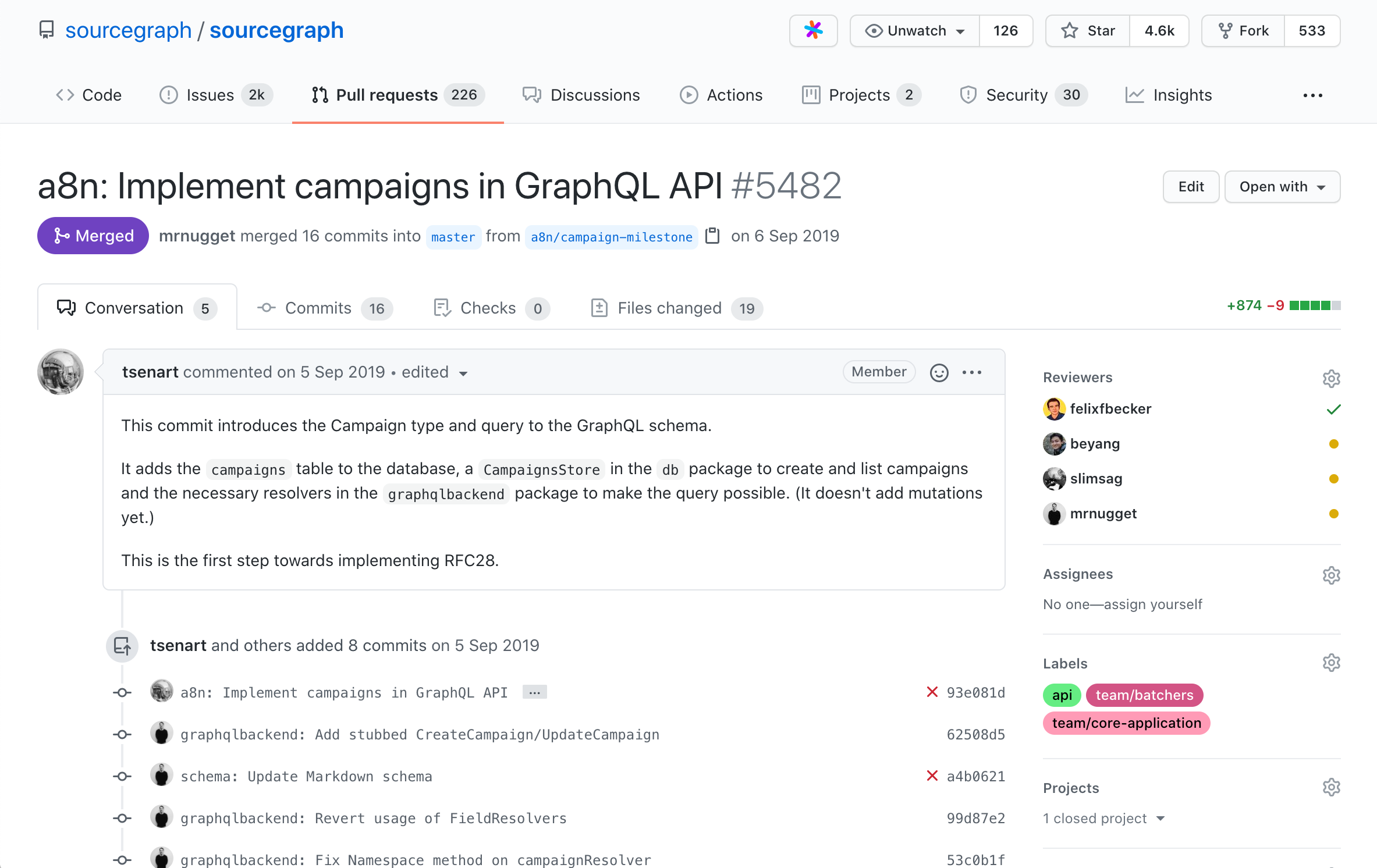

Pull request #1: Build one to throw away

In September 2019 we started working on Batch Changes, except that back then it was called Automation and it was already implemented, kind of. Quinn had built an impressive prototype to show to customers and to ask them whether they'd use something like this. More than one said "yes, I would, and exactly like that." "Build one to throw away" is what they say — but do you? Do you really throw away a prototype that's more than 10k lines of code and that customers pointed at and said "I want this"?

We did with this pull request; a placeholder for all of the code we wrote in September and October 2019 to rebuild the functionality of the prototype from scratch.

What made us do it? We came to the conclusion that building the product from the ground up, thereby fully understanding and owning the code, is more important to the long-term success of the project and the team than merging a prototype to get something out there as fast as possible. From my perspective now, this was one of the key decisions that helped us avoid accumulating large amounts of technical debt even though we've constantly shipped new things.

Only a few months later, though, we were stuck. We realised that what we built and shipped as an alpha to customers just didn't work on a conceptual level. In that version, Batch Changes (called Campaigns at the time) were executed on the Sourcegraph instance to produce changes in repositories. This was cool from a technical standpoint but it felt clunky and slow, and extending which types of changes could be made required us to add new code. "Meh" is a good word to use here.

So at this point we had thrown the prototype away, built the product from scratch and had to realise that, well, this isn't it. So what did we do?

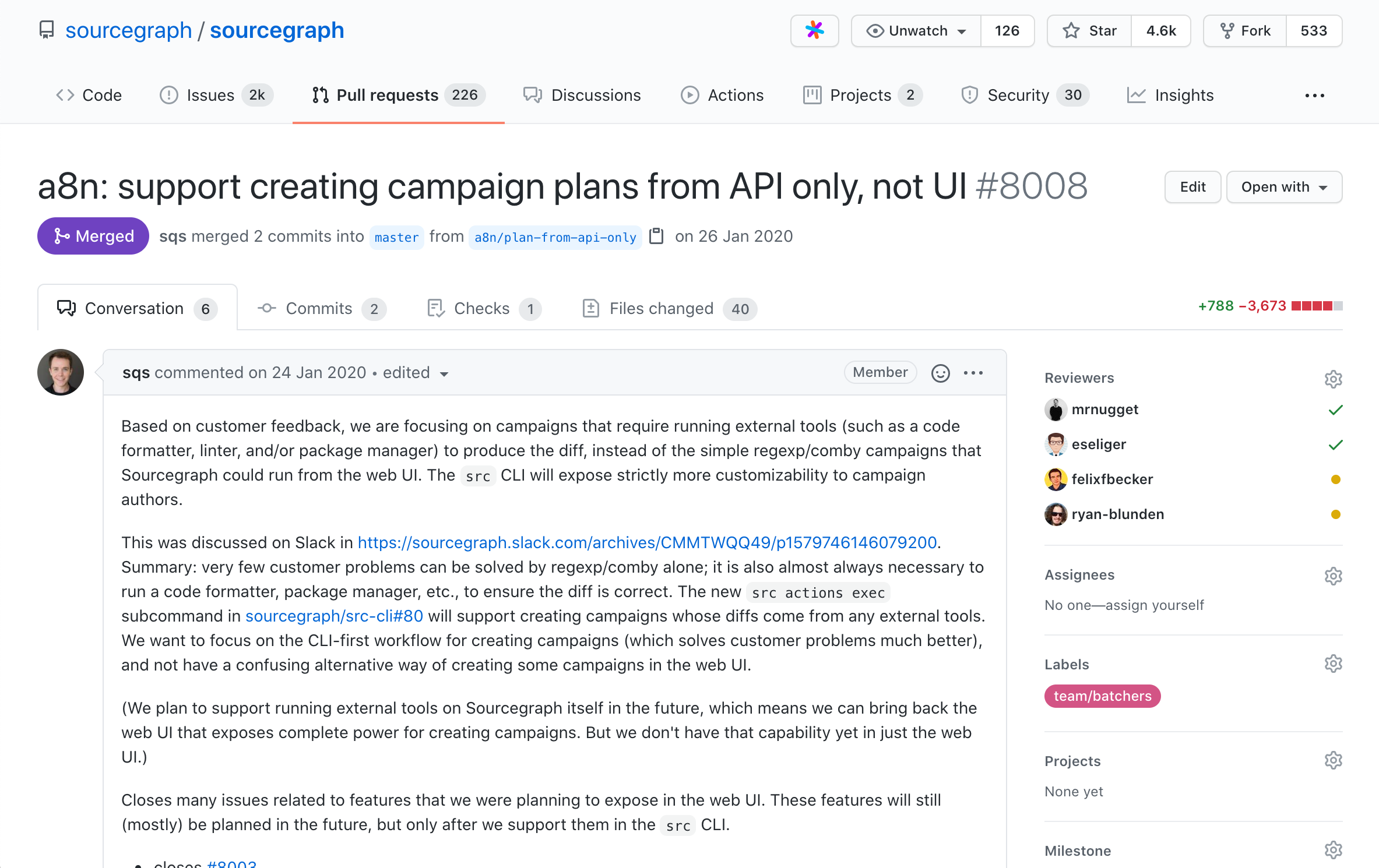

Pull request #2: Halfway there

We threw half of it away. The trigger was this idea: what if we simply don't produce changes on the server-side but instead accept diffs through the API and, as part of the Sourcegraph CLI, provide a tool to produce those diffs wherever you can run the CLI with whatever Docker container you want?

The server-side would then only half concern itself with diffs: how to publish them on code hosts as pull and merge requests, how to sync them, how to track them, how to rate limit their creation, etc. We wouldn't have to ship a new release every time we came up with a new way to produce diffs, and our customers that were most interested in making large-scale changes often had custom tooling already. With the CLI producing diffs by running any Docker container, we could give them a place to plug it in and make it large-scale.

This radical change to how the product worked was, in my opinion, maybe the most important one made in the life of Batch Changes. The mental model and the abstraction layers it introduced turned out to be incredibly well-fitting. They allowed us to go faster and get a valuable tool into the hands of our customers even earlier.

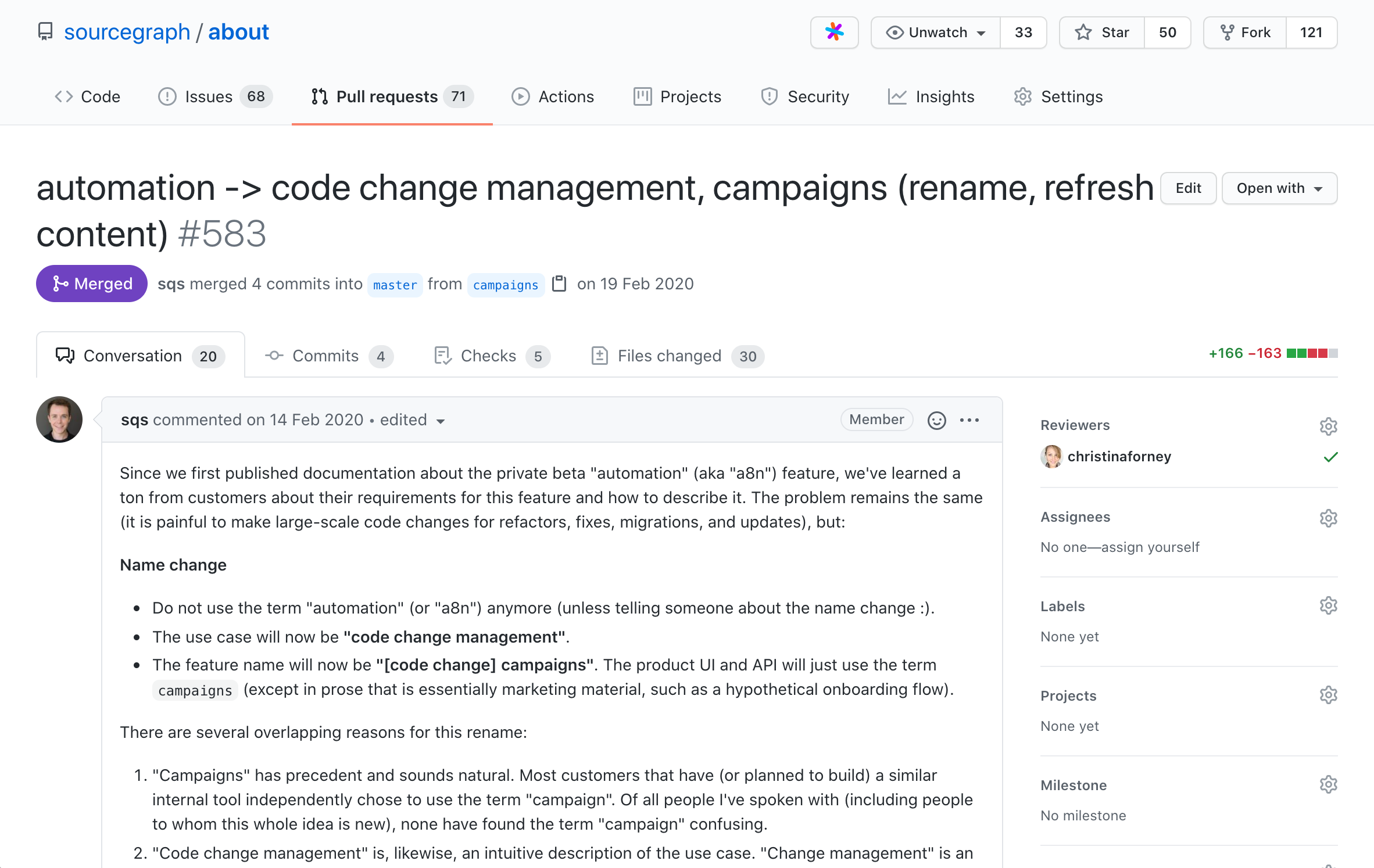

Pull request #3: Naming is hard

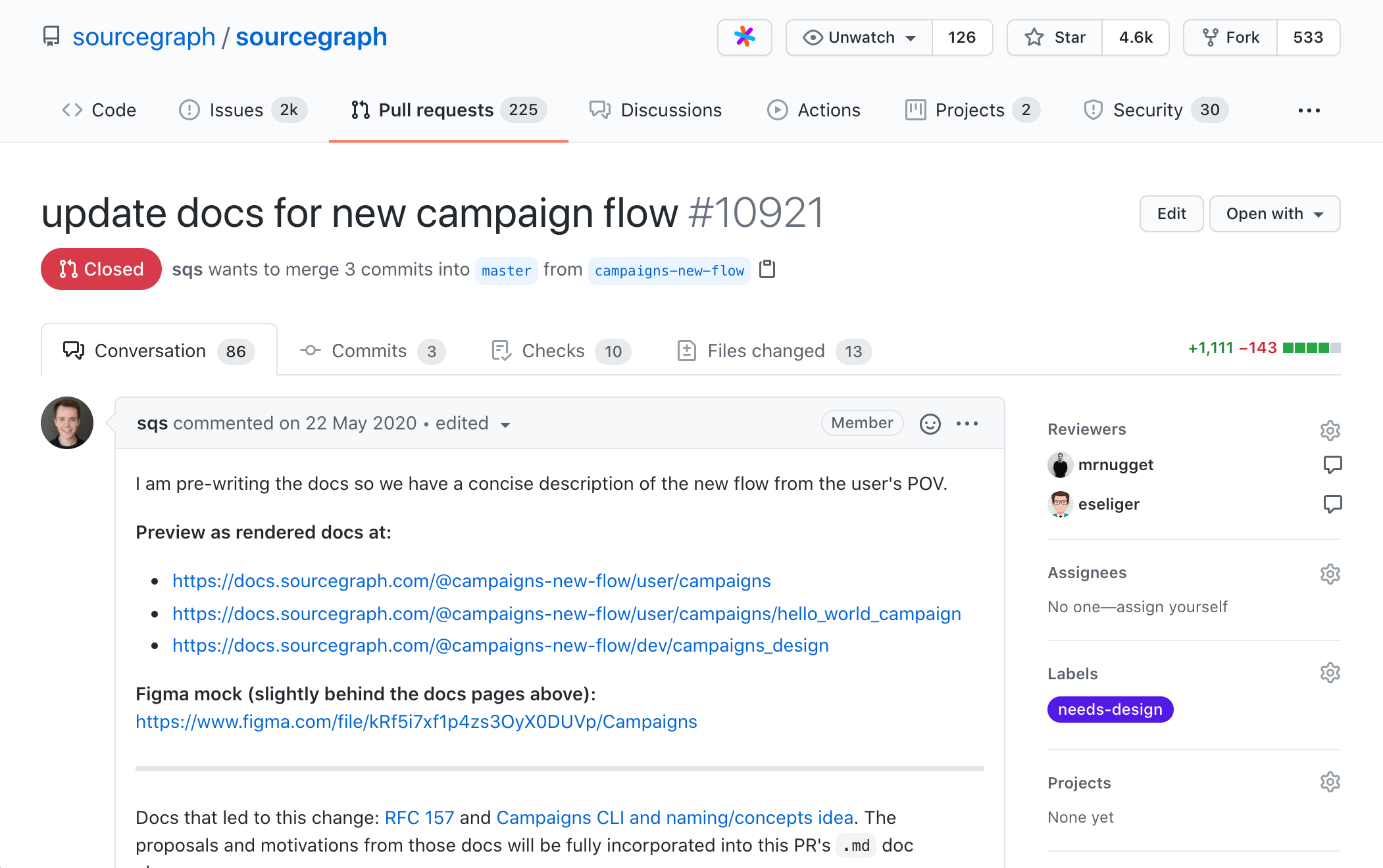

So far, so good, right? Yes, except, you know, naming is hard. While we could've gone with the old name for the feature (Automation), we decided to rename it. Take a look at PR #3 for the first of many PRs in February 2020 that changed "[Aa]utomation" to "[Cc]ampaigns" in our codebase.

What followed were months of fine-tuning, user testing, shipping, tweaking–i.e. iterative software development. We added more features, fixed a lot of bugs, and made things go faster.

Pull request #4: Switching to a declarative system

But (and by now you should know where this is going) something felt off. While Campaigns worked and we had customers using it and saying they loved it, we also noticed that our colleagues had problems using it, often hesitating to admit that they were confused with the workflow. Some of the questions we got were: why JSON (yes, we made users write JSON by hand)? Why can't I put everything in that JSON file? Why do I have to switch to the web UI? And, what if I want to update the changes?

I wouldn't say we were stuck again; we were constantly shipping new features and improvements. But it also started dawning on us that maybe we've exhausted one idea. Tweaking wouldn't get us out of this, nor would a sledgehammer. But maybe if we look at it from a different angle? What if, instead of requiring users to say what should happen to produce a campaign, we switch to a declarative model and let them describe what the campaign should look like in a YAML file?

This pull request shows how we asked "what if?" What if we wrote the documentation first (yes, README-driven development) and showed it to teammates and colleagues. The time it took a colleague to go from "ok, tell me what Campaigns are," to "ohhh, I get it, nice!" was reduced tenfold. This was very much to our relief since the changes necessary to make the documentation a reality were huge. We had to build a distributed, declarative system that manages hundreds or thousands of pull and merge requests across different code hosts.

Once the idea was validated by a lot of "this totally makes sense" from potential users, we got to work. Look at this PR, number 4b in this series if you will, to see an example of what "declarative" means and how we reconcile the current and the desired state (as described by a user) of a changeset. (Sidenote for the curious: the code today is even cooler, take a look).

That brings us to the last of the five pull requests.

Pull request #5: Naming is really hard

Towards the end of last year we ripped the "beta" label off of then-named Campaigns and started to concentrate on getting more customers to use it: writing better (or in some cases any) documentation, improving the onboarding process, providing troubleshooting help, and fixing bugs and edge cases.

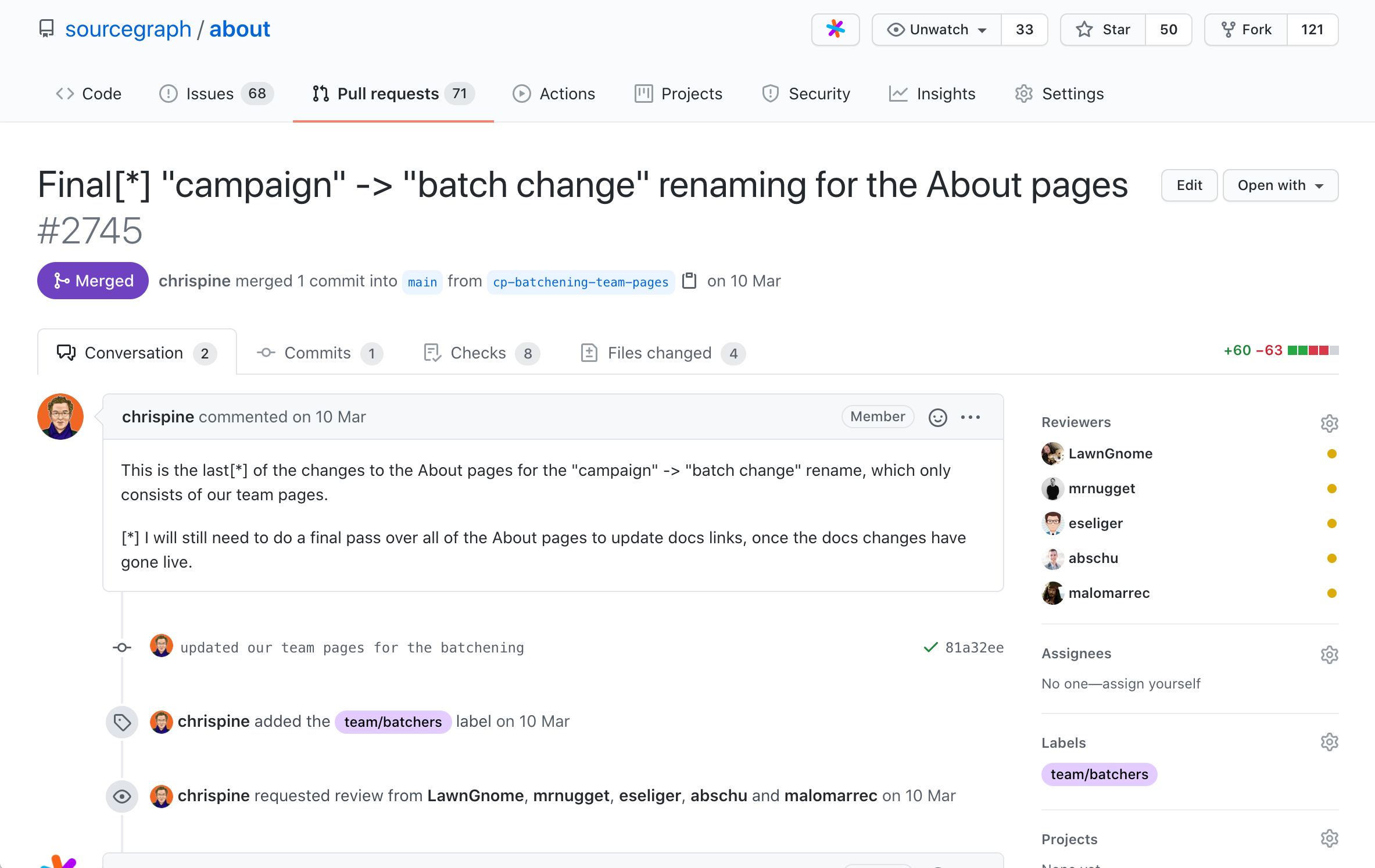

At the same time, our fast-growing product marketing team started working towards making our product as a whole more consistent. One thing that stood out was the name "Campaigns". Next to the names of our other features, it didn't fit in. It also always required a sentence or two of explanation. ("Glad you asked. A campaign is a ...") In a data-driven approach to finding a new name, Batch Changes came out as the winner. Ahead of Campaigns, Batches, Clusters, Bulk Changes, and others. No one we asked in our survey needed an explanation, and nearly everyone understood what the feature was roughly about.

But renaming what we built again? It would've been tempting to answer with "customers are already using it, why bother?" or "we've recorded demo videos with the old names!" or "there's so many screenshots we would need to change." In all honesty, though, we had to admit that existing customers probably wouldn't mind as long as it's not a breaking change. Some of our screenshots were outdated already, and we'd been meaning to record an up-to-date demo video anyway.

So, rename it we did and followed it up with the first official, non-alpha, non-beta, download-it-now-and-try-it launch of Batch Changes.

Commitment is the key to iterative software development

Looking back over these five pull requests and at the past 1.5 years now, I'm still surprised. I know how easy it is to say, "but this is what we said we wanted to build," or "but we invested all that time!" I've worked in iterative software development all my life. Two week sprints, four weeks, Agile, Scrum, even (ugh) SAFe. The danger of getting stuck and not knowing how to get out of it is always there. I'm still not quite sure how we avoided that trap. My best guess (and this will sound cheesy) is commitment. Commitment to building an excellent product, and commitment to building something that provides value to customers even if it means starting from scratch when you realize you're at a dead end.

Or let's turn this around. How hard was it to say in January last year, after a team of engineers had spent months building it, that we need to rip out half of it and change the flow completely? Really hard is my bet. But we did, and that still inspires and motivates me because I'd rather build and ship something that is valuable and that is good than to give customers something just because we built it.